Adapted from a journal entry, sometime in the blur that was 2020—

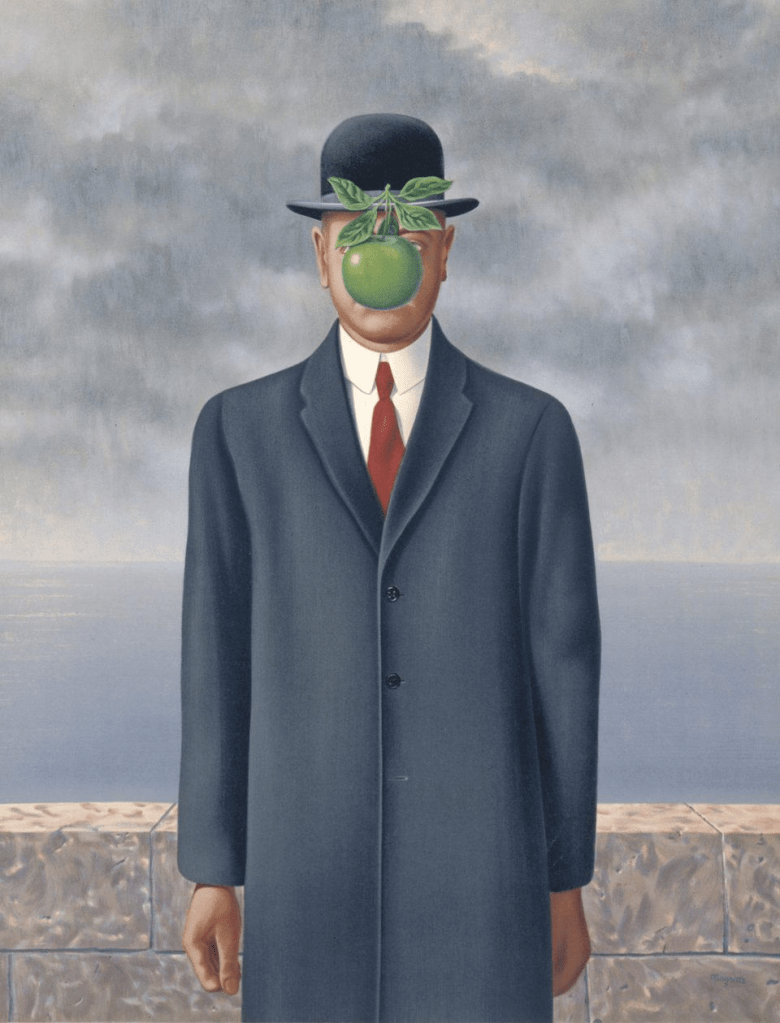

The Son of Man, A Self Portrait by René Magritte

The other day I was working with Ryser (my then six-year-old son) on some simple math problems because #COVIDCLASSROOM2020. On a worksheet was a group of apples. The first question was How many apples are there? Ryser responded, “lots of ones.” I asked him what he meant. He said, “that’s one apple, that’s one apple, that’s one…” and so on. I almost corrected him with conventional notions of addition, but I stopped myself and ended up explaining to him why he was right and conventional mathematics was wrong. It occurred to me that Ryser still saw the world as it truly is, in all its particularities, and I did not want to aid in his loss of innocence.

Ryser was seeing the personal creative form of the divine λόγος (logos, word/identity) in the particularity of each apple, each a unique “fingerprint” of its Maker. The question of identities has been observed and described in various aspects from various standpoints, some attempting to generalize, others to particularize, but all observing parts and wholes and relations the sum of which, in the end, should lead us all back to the ability to see everything in ones, in my mathematical aesthetic judgment.

It’s what Plato first called “ποιότης” (poiotes, literally “whatness,” the quality that distinguishes this from that, orange from apple, orange from red, etc.), or what Aristotle called with a back-and-forward tilt “τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι” (to ti en einai, “the what it was to be”), or what medieval scholastics called “quiddity” (“essence” / “whatness”), or what Duns Scotus called its “haecceity” (literally “thisness”), or what Gerard Manley Hopkins’ called “inscape” (or “the thingness of a thing” according to Thomas Merton’s reading of Hopkins). Ryser was putting his finger on the distinct and peculiar identity of every created thing and being—precisely because it is a created thing or being.

Accordingly, I explained that numbers are purely abstract objects, which is to say, ideas. Objects can only be counted so long as they don’t refer to things like apples and oranges, which is to say, created objects, God’s ideas made flesh. How can this apple be added to that apple, when they are two different things, even if we call them by the same name? What exactly are we counting? Neither of them are, in any real sense, the same thing, not even two identical things—they do not consist of the exact same atomic makeup, neither do they nor can they occupy the same space as any other. They may be classified under one assigned name, given to whatever meets the descriptive limits associated with that name (e.g., you can count one group of Granny Smith Apples, another group of Fuji Apples, or you can group them together in a basket with a bunch of other entirely different seedbearing foods and refer to the whole damn thing as a “fruit basket.” Wild. Might as well throw meat and potatoes in there and call it a “food basket”—I digress), but this habit we have of generalizing and classifying also has the effect of blinding and dehumanizing. As the artist Pierre Bonnard once remarked, “the precision of naming takes away the uniqueness of seeing.” (By naming, he’s referring to classifying, not giving proper names, an important distinction—see below.)

There is of course utility, even a certain necessity, in classifying and quantifying a world of otherwise infinite differences. I need to know, for example, that “this” screw won’t hold up both ends of a 2×4, so I need another screw, two screws, to get the job done, and I don’t care to name each one of them by their unique quiddity. I also need to know that I have exactly four “children” when I’m doing a headcount at the park—and we make them all wear the same color t-shirts on such occasions precisely so we don’t have to look around for unique bodies and faces, much less essences and inscapes. We have to see people superficially sometimes, whether at the park or on the freeway. But are any of my children “the same thing” or “the same child,” or as my children are any of them interchangeable? Obviously not. As Radley reminds me every time I remind her:

Me: You’re my only daughter!

Radley: You’re my only daddy!

If I look at this “tree” and just chalk it up to “a tree,” I will fail to see “this” unique, one-of-a-kind thing; I will fail to see what stands before me, towering into the heavens, being entirely itself, in wonder and mystery and majesty. If I look at the mounting death toll in our current wars and see only numbers, abstract ideas, I have seen nothing. Even if I begin to think in so specific terms as the numbers of “people” who have died, I am still blind to this child, that mother, her husband. People dying means nothing. Even a “person” dying, nothing. Death is meaningless until it has a proper name, an unrepeatable, irreplaceable relation: my child, my mother, my Savior, the Son of Man.

How many people are there in the world? There’s one, only one. Lots of ones. Wholes, indivisible, each with his or her own dignity, uniqueness, identity. “The universe has as many different centers as there are living beings in it, and that universe is shattered” the moment a single center is lost (Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag, paraphrased).

There’s more I want to say about this, but it’s all too philosophical, and now I’m thinking about my children, each of them, one by one, and I’m sad. So this is all for now.

That evening—after Ryser reminded me about the way things really are—I included Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “As Kingfisher’s Catch Fire” for their bedtime readings. I’ll conclude here with the same, though it’s hitting quite differently now:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

Hello from the UK

That was fascinating and food for thought. I like your son’s “lots of ones.”

Kind regards

Thank you, sir!