Reflections

Sons of Barabbas

The wires, the impulses, the updates, the crowd

The glow of the unending other

Where once a mirror testified

In the courtroom—the Echo

But now

Only us

A Confession of Violence

This article was recently published at Asbury Theological Seminary’s Seedbed website (here) during the height of conflicts that precipitated largely from the Ferguson ‘incident’. Below is a revised and slightly expanded version that better qualifies the most salient points.

American Civil War by Georgiana Romanovna

As a person who regularly tries to encourage fellow brothers and sisters in Christ to try to spend more time concerning themselves with the Good News of Jesus than with the nothing-new-under-the-sun news of the mainstream media, I feel it is necessary at this time to acknowledge a certain need for followers of Christ to speak out publicly with a distinctly Christian voice in response to recent tragedies heralded in the headlines, especially in view to the increasing angst in our nation’s political and cultural climate.

For that reason, I have a confession to make. It is a confession of violence.

I was reminded this week of what Karl Barth once wrote in his journal at a significant turning point in his life and thought during the First World War:

“It is not the war that disturbs our peace. The war is not even the cause of our unrest. It has merely brought to light the fact that our lives are all based on unrest. And where there is unrest there can be no peace” (Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts, Eberhard Busch).

As fingers continue to point, defenses continue to rise, and the wilderness is increasingly populated with a rapid influx of expatriated goats (Lev. 16), I hesitate to say what I feel I must say, because I am quite possibly wrong. But with that disclaimer: I want to suggest that there is a very real possibility that the recent tragedies in this nation were not simply caused by a few bad apples in an otherwise innocent bunch. I have to consider at least the possibility that somehow the increased supply of violence in our culture is suited precisely to meet the increase of a cultural demand, of which we are all complicit.

Consider for example the current political circus. There have been no shortage of aggravated complaints and expressions of puzzlement over how, of all the people our nation could have produced, we ended up with Cruella Deville and Leopold II as the two representatives of our nation’s principle values and common visions. And yet, I can’t help but think we are just willfully ignoring the obvious and only explanation; namely, the reason we ended up with the current representatives of this nation is that they are most representative of this nation.

This is not simply a principle of democracy. It is a principle of the more decisive governing factor in our consumerist culture, the principle of supply and demand. We have been feeding on this extended campaign season with an irrepressible appetite. Media networks, profiting outrageously from our patronage, have risen to meet our demand, and we in turn rise to feed on the surplus (a few tweeting feuds, some scandals, and a delicious array of ad hominem attacks). All the while the people blame the networks for the results, while the networks blame the other networks, while the other networks blame the people. Everybody is taking from everybody and then turning on everybody. It’s like a group of smeared-mouth toddlers blaming each other for cookies missing from the pan, but actually it’s a lot more like a twisted praying mantis love triangle.

But all this misses the point, because it is not the candidates we support that have produced this conflict; it is the conflict we support that has produced these candidates. And, indeed, they were perfect candidates for the task.

I think I can say unequivocally, if only because it can be neither proved nor denied, that what has most resonated with this nation in this campaign is its unprecedented rhetoric of violence. A civil war of clumsy words and gasoline passions is raging throughout our nation. We’re not looking for representatives of social values—we’re looking for spokesmen of social angst. Rather than tuning in to anticipate campaign candidates debating principled arguments with regular appeals to the constitution, we tune in to anticipate a surface battle of candidates in the rhetorical coliseum, waiting for a champion to arise who proves most capable of weaponizing trivia and amplifying slander. Who will prove to be the biggest bullhorn for the mob? Who will prove to have the loudest arguments? Who will lead half of this country in a campaign of disgust against the other half of this country?

The nominees may not represent much of what we stand for, but they represent quite exactly what we stand against, which is why we ended up with the two candidates who are supremely competent at attacking the incompetence of the other. It has become far easier in our nation to rally people around whom they hate than what they love. The appeal that resonates with this country’s soul is a an appeal to our restless inner hostility, for which we are miserably fearful or passionately infuriated (a rather pedantic distinction), the only cure of which is blame or blood or some other sacrificial motif. But since we have long rejected “religious” categories to explain “secular” realities, we have nothing to sacrifice but one another. But far be it from me to suggest a source of our violence so outrageous as an existential need for atonement. Suffice it just to say it seems quite evident that we are a nation increasingly naked and commensurately ashamed.

Indeed, “the [violence] is not even the cause of our unrest. It has merely brought to light the fact that our lives are all based on unrest.”

But perhaps I should be more transparent. The truth is I was confronted by my own complicity with this restless violence this week in a way I wish I could have kept hidden from myself.

If I am uncomfortably honest, I must confess that I have grown completely numb to the pain of the wider world. I don’t think I qualify as a sociopath or anything, but neither will I suggest that I am an accurate representative of the human heart. I know my capacity for pride and self-indulgence, and I should only hope that by and large human nature is at least better than my nature. All that to say, when I read or hear about a person being shot or multiple people being shot or riots breaking out because of all the people being shot, I am sorry to say that that it in no way affects me, at least not in a way that elicits compassion. If I feel anything it is invariably a kind of distracted, yawning anger, which isn’t really concerned with human beings and in fact is quite amused with blood. But most of the time I just don’t care.

I don’t know if I have always been particularly numb to distant tragedies or if I am just particularly sensitive to local misfortunes that hardly rank anywhere near the level of “tragedy,” but the truth is I am more likely to weep with my son weeping while getting shots at the doctor than I am to weep over strangers getting shot at a distance. And I know this to be the case, because I did weep–just a few tears–a few weeks ago when my son got five immunization shots in a single visit, and I did not weep upon hearing about the five police officers killed in a single shooting–not a single tear.

Until this past week. This past week I was confronted with an unlikely encounter with compassion. While watching a newly widowed woman give a public statement regarding the injustice of her husband’s death, suddenly the camera panned over to a young boy (15) covering his face with his shirt. It appeared he was trying to restrain himself at first, but his efforts soon proved futile. He began to weep, loudly. Recognizing the moment’s need, supporters began gently escorting him off stage, at which point his tears found their deepest and purest interpretation in a simple and repeated lament: “I want my daddy! I want my daddy! I want my daddy!”

I think this was the first time I have ever felt real compassion for someone so removed from my everyday life. I am certain it is the first time I have ever wept with such a person so removed from my everyday life. But in that moment it wasn’t about what the cops had done or what the man had not done, or vice versa on either side. It was about the longing of a lost boy’s heart for the presence of a father who is forever gone. That felt too close to home in too many ways for me. And perhaps for a moment I became a little more human and discovered the possibility of a far-reaching compassion.

But my empathy was short-lived, rather short-fused. In a matter of seconds I was moved from a blooming compassion to disturbed desire. I found myself looking up information about the police officers. I am ashamed to say that I wasn’t looking for anything about a “fair trial” or “due process” or “the other side of the story…” I was looking for blood. It was irrational. It was I imagine the way I would act if something were to happen to one of my own children or tribe. At first, I just wanted that little boy to have his father back, but I got over it. Rather than wallowing in that boy’s hopeless pain, perhaps in truth just to alleviate my pain, or perhaps more likely to satisfy my wrath, I grew up. I gave up on the childish hope of redemption, and frankly I wasn’t satisfied with even the rational desire for justice. I wanted revenge.

At some point after scrolling through headline after headline in a trance I snapped out of it. And in a moment I was confronted by my own hypocrisy, my immense capacity not only for violence but for a kind of self-righteous violence, if not a kind of self-congratulatory violence. And as such, I was confronted with the fact that even (or especially) my life is based on unrest, that I have no raw materials within me for peace, because what is in me is death and death must come out in blood (Heb. 9).

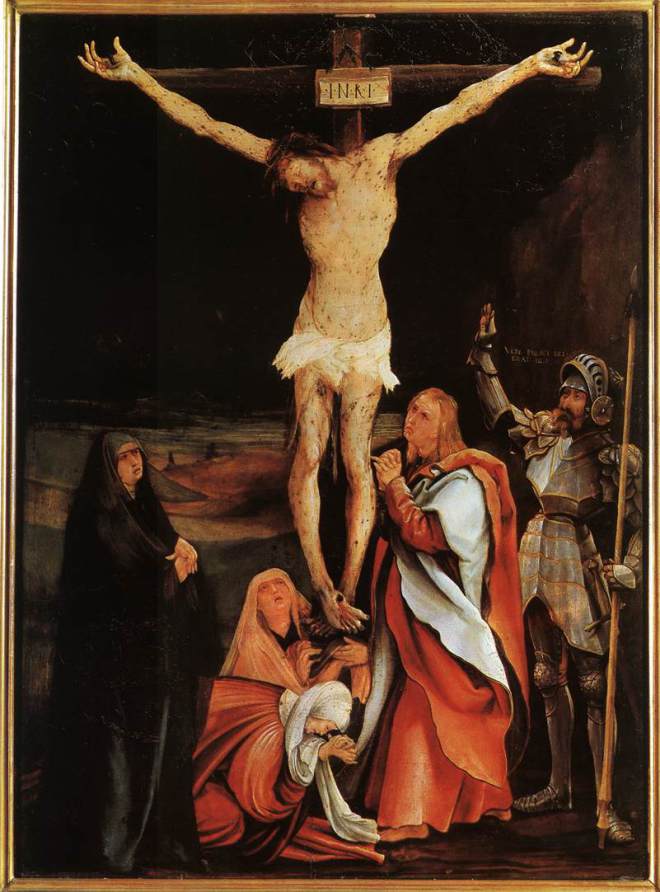

But rather than arbitrarily seeking it from a few cops I don’t know from Adam–or perhaps I know them precisely from Adam–I looked up to the print of Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece hanged above my desk, and I acknowledged where I must go for blood if I am ever going to find peace. For there is a Victim whose blood cries out from the ground with a word of Life louder than the word of Abel (Heb. 12:24; Gen. 4:10). But to go to him for blood, I must not attempt to take his side: I must go as the soldier with hammer in hand, for I am the reason for all this bloodshed, I have preferred Pilate’s basin to Jesus’, I am the executor of my own standard of justice, I am the restless criminal, I am the self-righteous murderer, I am the greedy thief, I am the hair-triggered abuse of power, I am the taunting spectator standing safely at a distance with no compassion for the pain of this Man and no tears for the sorrow his mother, for I have refused to be my brother’s keeper (Gen. 4:9) and instead have become his accuser (Rev. 12:10). I am the over-exacting vengeance I too often refuse to hand over to the Lord who demands that I do (Rom. 12).

So I surrendered: I handed over every last drop of my vengeance to him by way of an iron stake.

And I wept again. I wept for myself, for that boy, for my boys and my family, for that boy’s family, for that widow, for all those police officers and all their families and those widows, for all the restless souls caught up the violent whirlwind of our fire-breathing nation.

But I did not weep for Jesus. I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s because I didn’t feel worthy or maybe because he seemed too distant and strange. But maybe it was just the opposite. Maybe it was the first time I was able to weep with real compassion, the kind that refuses to give way to violence, because maybe it was the first time Jesus was able to weep through me.

Lord, have mercy.

An Inconvenient Truth

Judging by my last two trips through Chicago O’Hare, or as I like to call it, Hell: for future reference, I guess I should just factor in the cost of a hotel and rental car, as well as an additional 7 hr drive (not to mention the extra 2.5 hrs sitting needlessly on the Tarmac before cancelling the flight at 1:00 am, all the while being scolded by the flight attendant who continually insisted that I keep my one-year old–who was then on his third airplane in the last 12, 13, I don’t know 15 hours(?)–in my lap, because it’s dangerous…because there’s lightning outside…).

Or so went the thoughts I was mulling over in my head last night as I lay in our hotel bed, fuming. And then an unsolicited memory came to mind: the testimony of a Syrian family who stayed with a family in our church, the image of the father of that family having to shield his children’s eyes from the bodies lying all over the place as they aimlessly ran from snipers at the border, of the same father having to throw his children over a fence just hoping they wouldn’t get shot midair, of the same father who upon my welcoming to America said, “We love America!”

And so I rolled over and with utter insincerity to how I felt, but utter sincerity to what I knew to be true, made my last comment to Keldy on the situation before going to sleep: “We still have so much to be thankful for.”

#perspective #butistillhateairports #especiallyohare/ell

“Make Disciples”–Said Jesus Never

Small God in A Big World

Harold and His Purple Hell

Harold and the Purple Crayon is the saddest book ever written, also the most transparent. It is either a book about a lost son or a book about every man. It begins with scribbles on the first page. We are entering the story on the other side of some unnamed conflict. Order has given way to chaos. Something has gone terribly wrong.

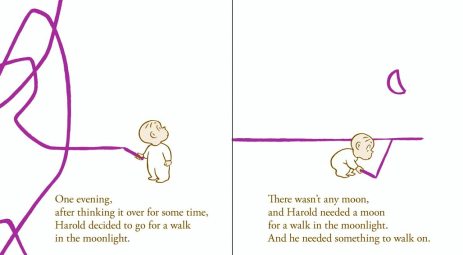

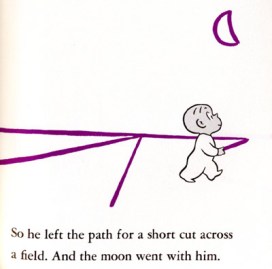

But then: stillness, as if suddenly removed from a world outside his control, into quite something else. Harold looks away to the night, turning a blind eye to the domestic disturbance behind. He is free. He can now escape into the world of unfettered creativity. The night is filled with endless possibilities. Harold has a crayon.

So Harold leaves home to follow a moon of his own making, reflecting his own light in a world built around a moon. He descends on a two-dimensional plane in search for he knows not what. The world is a surface, a canvas for his self-expression. He has been crowned with a purple crown as creator, author of life–all ultimately autobiographical–beginning by being scribbled out onto a blank canvas with no edges, no limits, the pure and unbounded freedom of the will.

Thus, Harold begins by making a place to stand, the ground beneath his feet, and the light for his path. Naturally, it begins straight and narrow, but eventually, and just as naturally, he wanders off. Now the night is following him.

Eventually, he needs a companion–for it is not good for man to be alone–so begins expressing himself to find a suitable helpmate. But something foreign seems to be embedded in his memory, something that either looks nothing like him on the surface or quite like him beneath. We begin to see what has been lurking about in Harold’s heart. It is an image curiously familiar in Western culture, an artificial fruit tree protected by a very real monster.

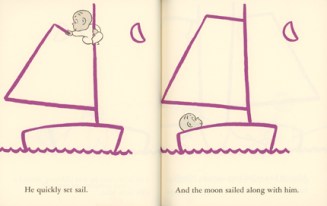

He creates a monster to guard a secret tree but discovers that the monster has a mind of its own and is no respecter of persons. The thing that was inside him now tried to eat him! Driven away in a panic by the creature of his own making, Harold accidentally draws a great deluge but thankfully saves himself on a boat. It is still night.

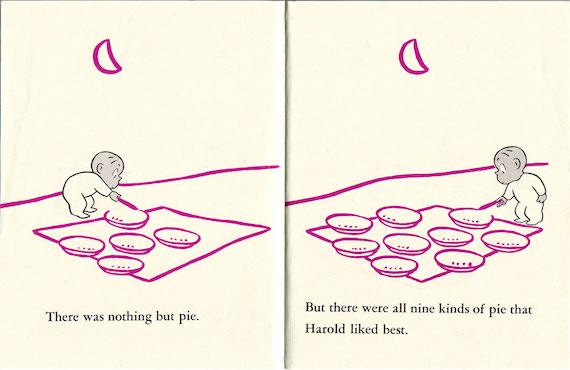

Harold makes it to land. He is famished. So he listens to the voice of his appetites to instruct him in his need for nourishment. Harold lives on pie alone.

Turns out he’s got god-sized eyes but only a human-sized stomach. He is left with a surplus of sweets. The producer creates consumers. From the surface of things, you’d never imagine this entire economy were born of a lost little boy’s aimless appetites. It all seems much happier than hunger. Everyone smiles at the pies—of course they smile—because in Harold’s world everyone is starving.

Harold feels sick. Maybe it was the pie, but it seems closer to the heart than the gut. He decides to start looking for home. He proceeds to draw a tower reaching the heavens. He now begins search for home. But his search never leads him to turn around, to go back, to regress and become like a child. His search leads him upward and onward. But a certain gravity eventually pulls him from the top of his tower back down to the surface. The height of his power turns out to reveal only how far he could fall.

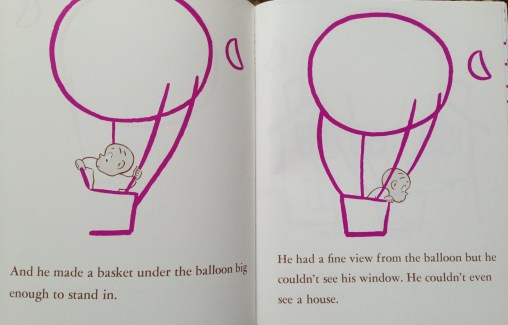

But he saves himself again by making a balloon. He has defied nature itself floating first and now hovering over otherwise abysmal conditions.

With no ground beneath him, however, floating seemed hardly any different from falling. This caused him to wonder about things like motion and the position of his moon–and the source of its light. But he did not bother long with that thought and drew new ground to stand on. He then thought Why not make make a new home? He drew it exactly how he remembered it, but it was still foreign to him.

But he puts his hand to the plow again, except not the plow at all. He is now determined, now in the big building business. He has set out to realize new horizons with raw materials of mud, metal, and imagination. This new creation has been liberated from the creations of the farm, rather from a life of fighting with thistles and praying for rain.

He has still not once considered turning around. Even if home were behind him, there’s no reason to believe he could go back. Time doesn’t work that way, nor the human heart. He can no longer believe that the home he remembers in that latent longing is one he actually belongs to. It is infinite progress, not ancient memory, that must satisfy his eternal longing. So the cure for his aching existence must come by way of forgetting, for while ancient memory always seems to haunt every present moment, it still feels somehow more distant than the ubiquitously advertised future that is forever at our fingertips.

So Harold tries to give form to the haunted hole in his heart in order to create a home to belong to. He builds more windows, hoping against hope that he will discover through one the bedroom mirror hanging on the inside of his bedroom door at home. He builds an entire city. And in the saddest scene ever illustrated, an anxious little boy climbs his towers with crayon in hand making a kingdom of windows that only reveal the gaping hollow of his homesickness.

It’s as if all of human life were born out of some grand front porch that continually expands in the heart with age. And all we know to do is try to match its grandness with grandiosity. So white-knuckled men scrape the clouds in high flying homes that feel nothing like home. They feel like heartache. But they are not dressed like heartache. For that, one need only to visit the real lifeblood of any city, its subway. The grandiosity of the surface is deflated in its subterranean confessional, where the height of human reach above is curiously incommensurate with height of human beings below. Down there, it feels like an entire world that has been shrunk to an embarrassingly navigable size. Everyone knows exactly where they are going, though never feeling any less lost. This is why it is impossible to ride the subway without wanting to cry a little. There is something human there and something missing. There is proximity, and there are infinite distances. The city somehow feels at once like being in control and being in a cage. It is the longing for the divine economy and the consolation of towers of human trade.

Harold’s heartache creates an entire city the size of his homesickness. But it didn’t cure it. It is the saddest picture I have ever seen.

But Harold finds help. He turns to a law enforcement officer for help to find his way home, but he is no help. All he can do is enforce the law, which simply reinforces Harold’s constitution of self-governance. Harold must stay the course. To turn back would indeed be unconstitutional.[1]

So he settles. He can neither find his home nor the light of day. He looks up to the lesser light of the night and wonders what makes it shine. He looks down again and sees his shadow, and continues to follow it.

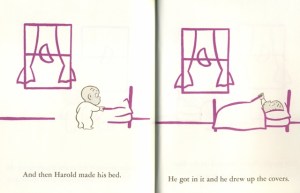

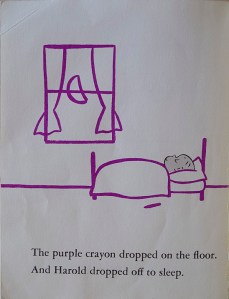

Harold’s home will be framed around the endless night, his only vision of light, something like the vision in Plato’s cave–before the liberation. Refusing to turn around he will never discover the genesis of his sight, the very warmth that always seems to hit him from behind in the memory of a home he no longer can believe is real. So he exchanges the future for the past and builds a shadow of the home he longs for. He is now on the other side of that empty window in which the moon is forever imprisoned.

The story ends with the end of all possibility. Harold is not only given to the night, but any possibility of the morning with him. Harold will slip into oblivion, but only because he tried to create his way out of it. The only thing worse than embracing emptiness is denying it, which is the difference between the nihilism of creation and creation in nihilo, between hopelessness and false hope, between godlessness and the no-god, between an honest heralding of despair and today’s bullhorn gospel of progress: between the fall of Adam and the rise of Babel.

It is the far end of self-expression in the triumph of self-discovery, the absolutization of human freedom in rebellion to the Light. Harold has succeeded in constructing his hell.

Hell is the life that immortalizes emptiness as its god and when the paint dries will live forever in its image.

The book concludes thus:

“The purple crayon dropped on the floor. And Harold dropped off to sleep.

“The End.”

Indeed.

O jealous moon

Don’t turn your back

That glory behind

Is a shadow of blackO jealous moon

Love the light as yourself

If seek your own glory

You’ll become something else

_________

Endnote

- Human freedom conceived of as the freedom of choice itself, rather than the freedom to choose the Good, is what the biblical creation account refers to as the freedom to eat from the knowledge of good and evil. To affirm freedom as such is to commit the primal sin, because it is determining what is good without reference to God, the absolute Good whose ‘self-expression’ alone is “very good” (Gen. 1:31), and elevating the contingent self’s will to ‘express itself’ in a groundless realm of a self-centered goodness with no shared referentiality, and thus outside of the realm of love. In such an ‘outer darkness’ there are no stable self-transcendent coordinates that can be identified as ‘good’, and thus the exercise of the will itself becomes the absolute good, that is, the will to power (Nietzsche).

- The Triune God’s goodness is expressed in love, which is always self-transcendent and self-fulfilling, always, as a whole, to love and be loved, always including self and other in a shared goodness. Thus, God’s absolute freedom is co-inherent with God’s absolute goodness, not the effervescent collision of a Heraclitean flux, nor the all-consuming Parmenidean Self for whom all otherness is mere illusion and at best, in the end, Nirvana, nor even the compromised synthesis of a very large and progressive Hegelian circle (even if conceived as a straight line).

- And thus human freedom is essentially the power of the will to love, which is precisely the power of the will not to. But the power of human freedom, the power of the Imago Dei, exercised in opposition to love is the essence of nihilism—just as God would be the first two die if the Persons of the Godhead erupted against one another in civil war.

- Harold had discovered this raw freedom on the first page, but by this time he has created an entire civilization based on its irreducible nucleus he has discovered only the utter isolating effects of his self-centered will to power. And so the human family created in the image of the Triune God parses out into pixels, gathering only on the highly volatile principle of the sovereign will of everybody’s one-person world: nuclear fission in the nuclear family, the death of God and so of us.

Sprinkled With Wisdom: Learning Across the Doctrinal Spectrum

Pondering infant baptism, believer’s baptism, and the need for Christian unity in an increasingly divided world. The topic is trending on my buzzfeed (#not), so I figured I’d chime in.

—

As someone serving in a denomination that does not baptize infants, and as someone who at the end of the day remains basically convinced by the best arguments for believer’s baptism as the normative mode of Christian baptism, I was compelled to reconsider the issue the other day when I observed in the Great Commission text (Mt. 28:18-20) that Jesus commands his followers to “disciple (v., imperative mood) all the nations,” and not, as most translations read, “make disciples of all nations” (see reflection on the Greek text of Matthew 28:18-20: “Make Disciples” Said Jesus Never“; for a sermon that addresses the issue: Disciple Is A Verb).

There are any number of implications that follow from turning the verb (and indeed the only imperative/command in this text) into the object of a verb that is decidedly not in this text (“make”). I think the wooden translation of Jesus’ command (to “disciple all the nations”) opens up support for the infant baptism position, because the participles “baptizing…and teaching…” aren’t modifying the object of discipleship but discipleship as such. In other words, the question is not What qualifies as a disciple? but rather What qualifies discipling? If the question is What qualifies a disciple, then the answer will have to draw a hard line between a disciple and not-a-disciple (which has no doubt contributed to the conflation of the definitions of “disciple” and “convert” in English parlance). That line, for many, is baptism.

But if the question is What qualifies discipling, which seems to be the answer Jesus is giving whether we’re asking the question or not, then his answer in Matthew 28 is: baptizing in the name of the Triune God and teaching to obey all he commanded.

As such, the Great Commission should function to qualify what constitutes a true discipling community (a church) and only derivatively to qualify what constitutes a true disciple. Only Jesus can determine who is truly his disciple, or not (cf. Jn. 8:31). The church’s job is not to make that determination but to do what Jesus commanded us to do, trusting that he will accomplish his will through it. He commanded us to disciple, not make disciples, and to do that by baptizing all nations in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit and teaching them to obey all he has commanded.

In other words, it is clear that the Church must baptize people as a means of discipling people, but we are not given any formal criteria for baptizing people. We are only given a theological condition (later particularized by Paul) that ensures we communicate the Name of the God into whose life the initiate is being baptized, in whose life the Church participates, because it is from that Name the children of God are given their own–as children (cf. Jn. 1:12). The meaning of baptism is far more important than the mode of baptism. Baptism should thus be regarded a means of discipling, not a qualification of a disciple, and its essential meaning has to do with preserving and extending the (Trinitarian) Name of God from which the believing community and its members derive their name (re: identity): “baptizing them in the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit” (Mt. 28:16-20).

—

But I can’t help but think that perhaps the lack of specificity is intended precisely to be suited to the task of discipling “all the nations” (Mt. 28:19). Remember, this is at the dawn of the Church, a people God envisages consisting of peoples from ‘every tribe, tongue, and nation’, whose universal message of salvation comes precisely through the local Gospel of Jesus Christ, King of the Jews, Lord of all. The Gospel to all nations would thus need, it seems, an initiation rite that is just as translatable as the Gospel to all languages: indeed, the Word of God itself testifies to the Gospel of our Hebrew Lord who spoke Aramaic, whose source documents are written in Greek and will eventually be translated into every language on earth.

In other words, God seems to have done everything possible to situate the Gospel within a variety of cultural expressions (hence the “fullness of time” Paul spoke about was a time when Judaism had been Hellenized within an all-but-consuming Graeco-Roman culture) and to preempt our tendency to divide over secondary and tertiary matters of form rather than uniting over matters of content (or mode vs. meaning). We have the Creeds and the Canon to delineate the people called the Church, and therein we have the most explicit and emphatic command to be a united people as such. But how often has God’s vision of ‘all tribes, all tongues, and all nations’ been shriveled up to many sad and disparate partisan visions of our own. How often have we exchanged harmony for homogeneity.

Could it be that Jesus was not too concerned about contextual forms so long as they were adapted to adequately communicate the internal theological content? Could it be that to take too rigid a position on this matter would be to take the only position that is definitively in error, because to do so would encourage disunity among those who have been baptized into the Name of the One True God, an implicit violation of the only explicit condition given with the command to baptize?

So perhaps we across denominational lines could do our best to embrace the communicative value of, especially, baptism and the Lord’s Supper, the two fundamental sacraments, which St. Augustine referred to as “visible words,” largely based on the way Paul uses them: as embodied Gospel communication (“as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Cor. 11); “you were baptized into Christ’s death…” (Rom. 6)). The salient matter, then, is that we need to make sure whatever contextual forms we adopt in the administration of the sacraments, we do our best to adapt those contextual forms to their theological content in our effort to communicate the Gospel faithfully. This can be done well or poorly no matter what the age or agency of those being initiated. Being on the “right side” of such issues too often provides us with the excuse to do the “right side” wrongly, or often at least carelessly and uncritically. How many services have you sat through in which sacraments seemed, quite literally, meaningless?

So we would all do well to consider with extreme care ways in which the baptism ceremony functions for the whole community as a “remember your baptism” ceremony: if every baptism is an identification with Christ’s death and resurrection, every baptism is in essence “one baptism” (Eph. 4:5) and is thus an opportunity to cultivate the corporate identity of the people of God as one Body with one Head, as well as the personal identity of believers as members of that One Body.

Imagine if the Church would begin thinking hard about understanding what we can learn from other positions across the ecclesial spectrum rather than thinking so hard about how to prove those other positions wrong. I’ll be continuing to reflect on what I can learn from the infant baptism tradition–it has been fruitful thus far. Lord knows the world has enough examples of people forming an “us” by pointing a finger at a “them.” May it not be so of the people whose Lord was broken so that we who are broken could be made whole, the people who have been taught to pray, “Our Father…” The Lord our God, the Lord is one. May his wholeness begin to restore our brokenness.

Mirror of Earth, Window of Heaven

“And so he was raised on a cross, and a title was fixed, indicating who it was who was being executed. Painful it is to say, but more terrible not to say…He who suspended the earth is suspended, he who fixed the heavens is fixed, he who fastened all things is fastened to the wood; the Master is outraged; God is murdered.”

Melito of Sardis (A.D. 180)

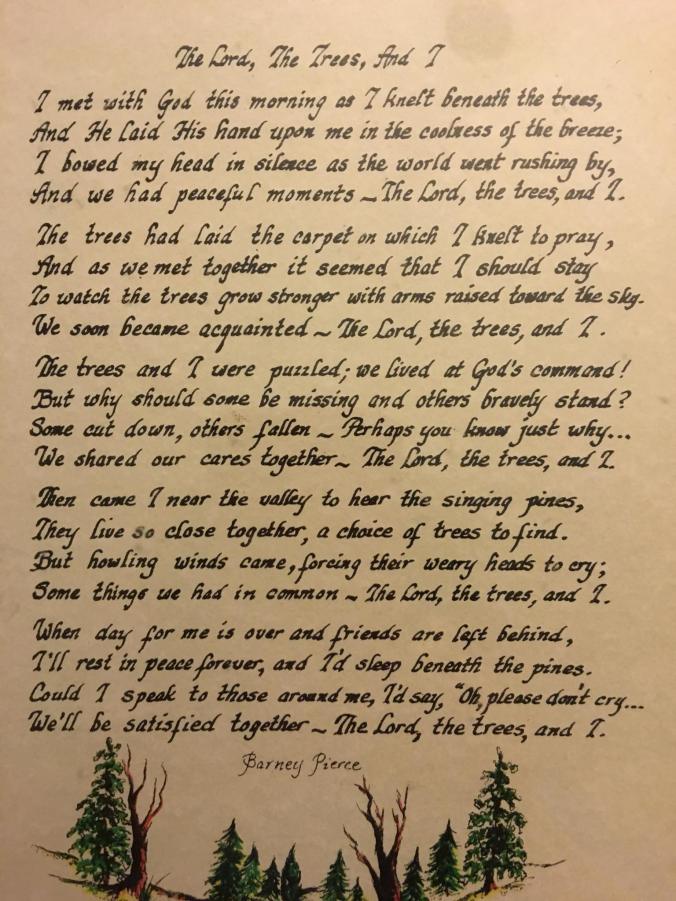

The Lord, The Trees, And I

With all the sharp-edged words flying around the airwaves like aimless shrapnel in a world of lost boys, I’m reminded by these now aged and well worn words that there is a sanctuary for all who are moved more by the howling winds of creation’s longing (Rom. 8:19) than they are by the passing winds of promise-panting change. There is still a hope that sinks beneath the surface and stretches beyond the skies, but it is a hope that makes no alliances with the pride and violence rolling off the tip of this world’s two-pronged tongue—for, indeed, there are things that simply do not belong in a Garden.

I’m not sure there’s anything left to fight for on the battlefield. Perhaps it is time to begin leading people back to the trees…