This article was recently published at Asbury Theological Seminary’s Seedbed website (here) during the height of conflicts that precipitated largely from the Ferguson ‘incident’. Below is a revised and slightly expanded version that better qualifies the most salient points.

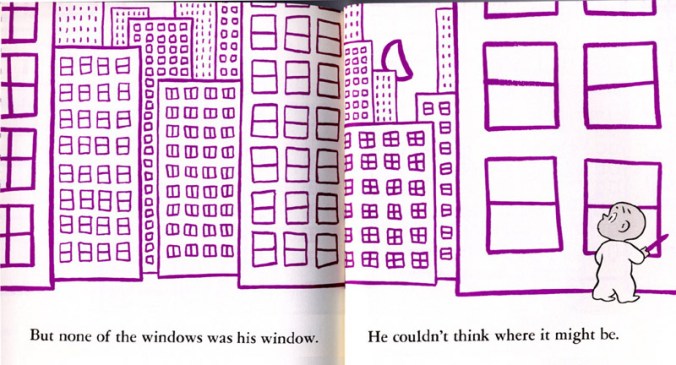

American Civil War by Georgiana Romanovna

As a person who regularly tries to encourage fellow brothers and sisters in Christ to try to spend more time concerning themselves with the Good News of Jesus than with the nothing-new-under-the-sun news of the mainstream media, I feel it is necessary at this time to acknowledge a certain need for followers of Christ to speak out publicly with a distinctly Christian voice in response to recent tragedies heralded in the headlines, especially in view to the increasing angst in our nation’s political and cultural climate.

For that reason, I have a confession to make. It is a confession of violence.

I was reminded this week of what Karl Barth once wrote in his journal at a significant turning point in his life and thought during the First World War:

“It is not the war that disturbs our peace. The war is not even the cause of our unrest. It has merely brought to light the fact that our lives are all based on unrest. And where there is unrest there can be no peace” (Karl Barth: His Life from Letters and Autobiographical Texts, Eberhard Busch).

As fingers continue to point, defenses continue to rise, and the wilderness is increasingly populated with a rapid influx of expatriated goats (Lev. 16), I hesitate to say what I feel I must say, because I am quite possibly wrong. But with that disclaimer: I want to suggest that there is a very real possibility that the recent tragedies in this nation were not simply caused by a few bad apples in an otherwise innocent bunch. I have to consider at least the possibility that somehow the increased supply of violence in our culture is suited precisely to meet the increase of a cultural demand, of which we are all complicit.

Consider for example the current political circus. There have been no shortage of aggravated complaints and expressions of puzzlement over how, of all the people our nation could have produced, we ended up with Cruella Deville and Leopold II as the two representatives of our nation’s principle values and common visions. And yet, I can’t help but think we are just willfully ignoring the obvious and only explanation; namely, the reason we ended up with the current representatives of this nation is that they are most representative of this nation.

This is not simply a principle of democracy. It is a principle of the more decisive governing factor in our consumerist culture, the principle of supply and demand. We have been feeding on this extended campaign season with an irrepressible appetite. Media networks, profiting outrageously from our patronage, have risen to meet our demand, and we in turn rise to feed on the surplus (a few tweeting feuds, some scandals, and a delicious array of ad hominem attacks). All the while the people blame the networks for the results, while the networks blame the other networks, while the other networks blame the people. Everybody is taking from everybody and then turning on everybody. It’s like a group of smeared-mouth toddlers blaming each other for cookies missing from the pan, but actually it’s a lot more like a twisted praying mantis love triangle.

But all this misses the point, because it is not the candidates we support that have produced this conflict; it is the conflict we support that has produced these candidates. And, indeed, they were perfect candidates for the task.

I think I can say unequivocally, if only because it can be neither proved nor denied, that what has most resonated with this nation in this campaign is its unprecedented rhetoric of violence. A civil war of clumsy words and gasoline passions is raging throughout our nation. We’re not looking for representatives of social values—we’re looking for spokesmen of social angst. Rather than tuning in to anticipate campaign candidates debating principled arguments with regular appeals to the constitution, we tune in to anticipate a surface battle of candidates in the rhetorical coliseum, waiting for a champion to arise who proves most capable of weaponizing trivia and amplifying slander. Who will prove to be the biggest bullhorn for the mob? Who will prove to have the loudest arguments? Who will lead half of this country in a campaign of disgust against the other half of this country?

The nominees may not represent much of what we stand for, but they represent quite exactly what we stand against, which is why we ended up with the two candidates who are supremely competent at attacking the incompetence of the other. It has become far easier in our nation to rally people around whom they hate than what they love. The appeal that resonates with this country’s soul is a an appeal to our restless inner hostility, for which we are miserably fearful or passionately infuriated (a rather pedantic distinction), the only cure of which is blame or blood or some other sacrificial motif. But since we have long rejected “religious” categories to explain “secular” realities, we have nothing to sacrifice but one another. But far be it from me to suggest a source of our violence so outrageous as an existential need for atonement. Suffice it just to say it seems quite evident that we are a nation increasingly naked and commensurately ashamed.

Indeed, “the [violence] is not even the cause of our unrest. It has merely brought to light the fact that our lives are all based on unrest.”

But perhaps I should be more transparent. The truth is I was confronted by my own complicity with this restless violence this week in a way I wish I could have kept hidden from myself.

If I am uncomfortably honest, I must confess that I have grown completely numb to the pain of the wider world. I don’t think I qualify as a sociopath or anything, but neither will I suggest that I am an accurate representative of the human heart. I know my capacity for pride and self-indulgence, and I should only hope that by and large human nature is at least better than my nature. All that to say, when I read or hear about a person being shot or multiple people being shot or riots breaking out because of all the people being shot, I am sorry to say that that it in no way affects me, at least not in a way that elicits compassion. If I feel anything it is invariably a kind of distracted, yawning anger, which isn’t really concerned with human beings and in fact is quite amused with blood. But most of the time I just don’t care.

I don’t know if I have always been particularly numb to distant tragedies or if I am just particularly sensitive to local misfortunes that hardly rank anywhere near the level of “tragedy,” but the truth is I am more likely to weep with my son weeping while getting shots at the doctor than I am to weep over strangers getting shot at a distance. And I know this to be the case, because I did weep–just a few tears–a few weeks ago when my son got five immunization shots in a single visit, and I did not weep upon hearing about the five police officers killed in a single shooting–not a single tear.

Until this past week. This past week I was confronted with an unlikely encounter with compassion. While watching a newly widowed woman give a public statement regarding the injustice of her husband’s death, suddenly the camera panned over to a young boy (15) covering his face with his shirt. It appeared he was trying to restrain himself at first, but his efforts soon proved futile. He began to weep, loudly. Recognizing the moment’s need, supporters began gently escorting him off stage, at which point his tears found their deepest and purest interpretation in a simple and repeated lament: “I want my daddy! I want my daddy! I want my daddy!”

I think this was the first time I have ever felt real compassion for someone so removed from my everyday life. I am certain it is the first time I have ever wept with such a person so removed from my everyday life. But in that moment it wasn’t about what the cops had done or what the man had not done, or vice versa on either side. It was about the longing of a lost boy’s heart for the presence of a father who is forever gone. That felt too close to home in too many ways for me. And perhaps for a moment I became a little more human and discovered the possibility of a far-reaching compassion.

But my empathy was short-lived, rather short-fused. In a matter of seconds I was moved from a blooming compassion to disturbed desire. I found myself looking up information about the police officers. I am ashamed to say that I wasn’t looking for anything about a “fair trial” or “due process” or “the other side of the story…” I was looking for blood. It was irrational. It was I imagine the way I would act if something were to happen to one of my own children or tribe. At first, I just wanted that little boy to have his father back, but I got over it. Rather than wallowing in that boy’s hopeless pain, perhaps in truth just to alleviate my pain, or perhaps more likely to satisfy my wrath, I grew up. I gave up on the childish hope of redemption, and frankly I wasn’t satisfied with even the rational desire for justice. I wanted revenge.

At some point after scrolling through headline after headline in a trance I snapped out of it. And in a moment I was confronted by my own hypocrisy, my immense capacity not only for violence but for a kind of self-righteous violence, if not a kind of self-congratulatory violence. And as such, I was confronted with the fact that even (or especially) my life is based on unrest, that I have no raw materials within me for peace, because what is in me is death and death must come out in blood (Heb. 9).

But rather than arbitrarily seeking it from a few cops I don’t know from Adam–or perhaps I know them precisely from Adam–I looked up to the print of Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece hanged above my desk, and I acknowledged where I must go for blood if I am ever going to find peace. For there is a Victim whose blood cries out from the ground with a word of Life louder than the word of Abel (Heb. 12:24; Gen. 4:10). But to go to him for blood, I must not attempt to take his side: I must go as the soldier with hammer in hand, for I am the reason for all this bloodshed, I have preferred Pilate’s basin to Jesus’, I am the executor of my own standard of justice, I am the restless criminal, I am the self-righteous murderer, I am the greedy thief, I am the hair-triggered abuse of power, I am the taunting spectator standing safely at a distance with no compassion for the pain of this Man and no tears for the sorrow his mother, for I have refused to be my brother’s keeper (Gen. 4:9) and instead have become his accuser (Rev. 12:10). I am the over-exacting vengeance I too often refuse to hand over to the Lord who demands that I do (Rom. 12).

So I surrendered: I handed over every last drop of my vengeance to him by way of an iron stake.

And I wept again. I wept for myself, for that boy, for my boys and my family, for that boy’s family, for that widow, for all those police officers and all their families and those widows, for all the restless souls caught up the violent whirlwind of our fire-breathing nation.

But I did not weep for Jesus. I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s because I didn’t feel worthy or maybe because he seemed too distant and strange. But maybe it was just the opposite. Maybe it was the first time I was able to weep with real compassion, the kind that refuses to give way to violence, because maybe it was the first time Jesus was able to weep through me.

Lord, have mercy.