Adapted from a journal entry, sometime in the blur that was 2020—

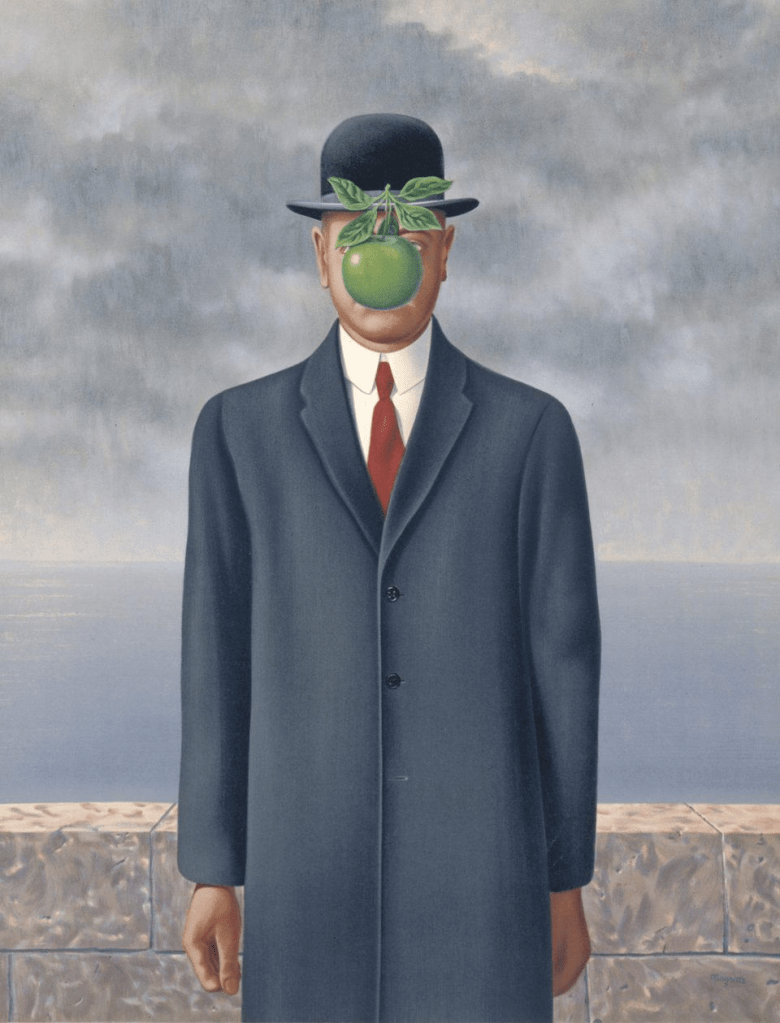

The Son of Man, A Self Portrait by René Magritte

The other day I was working with Ryser (my then six-year-old son) on some simple math problems because #COVIDCLASSROOM2020. On a worksheet was a group of apples. The first question was How many apples are there? Ryser responded, “lots of ones.” I asked him what he meant. He said, “that’s one apple, that’s one apple, that’s one…” and so on. I almost corrected him with conventional notions of addition, but I stopped myself and ended up explaining to him why he was right and conventional mathematics was wrong. It occurred to me that Ryser still saw the world as it truly is, in all its particularities, and I did not want to aid in his loss of innocence.

Ryser was seeing the personal creative form of the divine λόγος (logos, word/identity) in the particularity of each apple, each a unique “fingerprint” of its Maker. The question of identities has been observed and described in various aspects from various standpoints, some attempting to generalize, others to particularize, but all observing parts and wholes and relations the sum of which, in the end, should lead us all back to the ability to see everything in ones, in my mathematical aesthetic judgment.

It’s what Plato first called “ποιότης” (poiotes, literally “whatness,” the quality that distinguishes this from that, orange from apple, orange from red, etc.), or what Aristotle called with a back-and-forward tilt “τὸ τί ἦν εἶναι” (to ti en einai, “the what it was to be”), or what medieval scholastics called “quiddity” (“essence” / “whatness”), or what Duns Scotus called its “haecceity” (literally “thisness”), or what Gerard Manley Hopkins’ called “inscape” (or “the thingness of a thing” according to Thomas Merton’s reading of Hopkins). Ryser was putting his finger on the distinct and peculiar identity of every created thing and being—precisely because it is a created thing or being.

Continue reading